After recording and studying a song like “King William’s Son” I’m struck by the dichotomy of the singers of these ballads and the storied songs they sing. I’ll remind you that John Jacob Niles collected these ballads from isolated, rural areas of the southeastern United States.

So lest you think Niles somehow selected only high brow folks to collect ballads from, or if somehow you’ve yet to imagine how strange it must have been for Niles to hear talk of castles and the ocean while sitting in a forest in the middle of a land locked county, I’ll remind you: these songs all came from Southerners: they belong to us. We carried them over the sea.

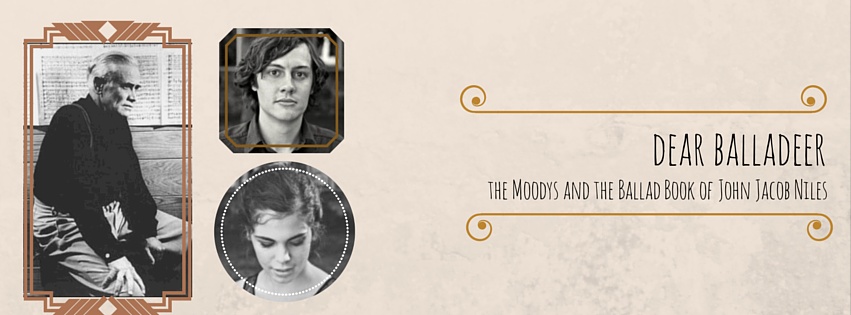

When Jonathan and I first read the ballad book, it was the collection stories as much as the ballads that struck us. The songs are haunting and beautiful, but it is the gift of the singers’ personalities, bestowed to all of us by Niles, that gives much of The Ballad Book its heart.

I’d like to focus on the singers of Niles No. 2, Uncle Brother Patterson, and Niles No. 4, an unnamed singer.

Uncle Brother Patterson, Niles tells us, was “a cattle drover…[who] had once owned a very fine farm” (Ballad Book, pg. 17). He lost his property due to some unnamed illegal transgression, and later ended up in a bloody brawl and was imprisoned (pg 18). Niles writes that after serving his term, Patterson found himself a vagabond, doing occasional odd jobs (18).

He had heard his noisy relatives sing the rather uninteresting “Parsley Vine” song, and to establish his position as a singer he took me aside and sang “The Shirt of Lace” very quietly and accurately. None of the Patterson men could read or write… My notes say: ‘A very interesting melodic line. The music in the family came from a Patterson grandmother, who emigrated from Virginia at the end of the War Between the States.’ ” – The Ballad Book, pgs. 18-19

Uncle Brother Patterson, immortalized in only a few short paragraphs, leaves a haunting impression. His troubled past, his desire to prove himself as a singer and learned individual despite his illiteracy, and the ballad he gave to Niles provide a complicated and striking portrait.

However, my favorite character thus far has been the unnamed singer of Niles No. 4. Niles describes her as a “tall, angular woman of great age” (Ballad Book, 28). She does not wish for Niles to publish her name due to “family difficulties and embarrassments brought down upon her by her children” (28). Niles informs us that she is now raising her grandsons.

More than her story though, it is the stark contrast between her diction and the song she sings. As already described, King William’s Son (No. 4) is a very complex ballad. Indeed, Child writes that his fourth ballad is likely the most common folk ballad of Europe, with numerous variants. (Generally, “Barbra Ellen” is considered the most common folk ballad of North America). The song takes place by the sea, in a castle; its actors are lords and ladies who speak poetically and articulately.

But Niles provides us with some of the singer’s own dialogue:

“If a body wants to be glum-faced…there always be lots of reasons for it. Why if I worked at it, I could be as sour as any straddle-pole politician in Franklin, North Carolina.” (28)

Later, she talks about her relationship with her grandsons:

“Them cute little fellers playin’ out yonder in that cow-stomp are my only partners now… they’s young enough to mind me, and they ain’t old enough to be a botherment – not yet.” (29)

For those long used to Southern stereotypes, such diction is not surprising. Her ballad though – so sad, so haunting, with roots so ancient – does render complexity and depth to our understanding of this unnamed character and Uncle Brother Patterson too. These two singers are not atypical of the myriad other characters John Jacob Niles encountered, who, despite little formal education, contained inside themselves the wealth of folk knowledge and fable, passed down these long centuries.

As much as our project is a tribute to Mr. Niles, it increasingly feels a tribute to these people he collected from too, for with each song a miniature resurrection takes place, and we find ourselves in the presence of a cast of characters long dead. They are the ghosts of the South, and it is their words we sing, their melodies.

If you will, sing along with us. Join your own warble, your own inimitable timbre, to the thousands of other voices who sang these songs before you.

You will find yourself, then, with us, and John Jacob Niles, and Uncle Brother Patteson, and the woman whose name we will never know. You will find yourself in the great loveliness of ghosts.